Every Principle Repudiated

How would you reach a whole generation of busy, work-oriented people with the gospel message? What would you do to get the attention of people, accustomed to compelling imagery in popular entertainment and worship, long enough to teach them about deeper spiritual things? How would you ever get across such abstract concepts as justification, atonement for sin, or the judgment?

This was exactly the problem that Moses was called to face when he took the leadership of over two million people, marching out of Egypt toward Canaan. They had spent generations in slavery; now they were ignorant of God’s will and prone to doubt and disobedience. They had a hard time understanding anything they couldn’t see—a life spent being threatened with whips produced a cramped mind and a degraded dignity.

Right after sin, God instructed Adam to offer sacrifices as a token atonement for sin. He promised that the Messiah would be born among the family tree of believers. As Adam’s descendants sacrificed a lamb, they showed faith in God’s promise of deliverance from sin. When Abel obeyed God’s instructions, he “offered unto God a more excellent sacrifice than Cain, by which he obtained witness that he was righteous” (Hebrews 11:4). Abraham got a better idea of what this meant, when God said he must sacrifice his own son. And the promises to Abraham were God’s way of explaining the gospel: “in thy seed shall all the nations of the earth be blessed” (Genesis 22:18; compare with Galatians 3:8, 16). But when Jacob’s sons settled in Egypt, the gospel picture, which had once been so clear, began to fade. A new Pharaoh came to power, and turned the Hebrews into slaves. Sabbathkeeping became difficult. To make matters worse, “on account of the superstitious veneration in which animals were held by the Egyptians, the Hebrews were not permitted, during their bondage, to present the sacrificial offerings. Thus their minds were not directed by this service to the great Sacrifice, and their faith was weakened.”1

At the same time, the popular religion of Egypt was very senses-oriented. Everything they worshipped was something you could see. Impressive ceremonies led by their pagan priests held the common people in superstitious wonder. And if you just wanted to have a “good time,” the deities of the day wouldn’t condemn your immorality—in fact, the golden calf scene at Sinai was just an imitation of Egypt’s cult festivals.

Under these circumstances, something drastic had to be done to impress upon the newly-freed Israelites a knowledge of God’s character and of His plan to save them, not only from slavery, but from the bondage of sin.

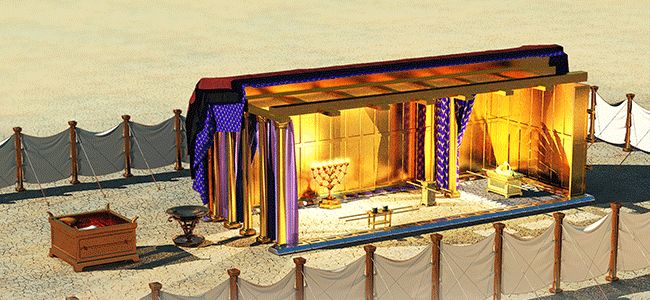

It is no surprise, then, that when Moses went up into the mountain, God outlined a system that would teach His people in more detail than had ever been revealed before. The solution? “Let them make me a sanctuary; that I may dwell among them” (Exodus 25:8). This would be God’s house in their camp, a house of symbols.

The sanctuary was to be at the heart of a new system of worship, which was rich in lessons about salvation and the Messiah to come. This system only built on the basic service, long forgotten or neglected, of offering a sacrificial lamb. But it added much more detail about the process of justification, and judgment, and blotting out of sin. We are still unraveling its myriad lessons today.

How do we know that the elements of the “tabernacle” represented a better, heavenly system? Moses was emphatically told to “make them after their pattern, which was shewed thee in the mount” (Exodus 25:40). And the apostle Paul notes that the Levite priests “serve unto the example and shadow of heavenly things” (Hebrews 8:5). This is just after he points out that Christ is our “high priest, who is set on the right hand of the throne of the Majesty in the heavens; a minister of the sanctuary, and of the true tabernacle, which the Lord pitched, and not man” (Hebrews 8:1, 2).

A brief outline of the meaning of the elements in the tabernacle services:

The Tabernacle’s Layout.The layout of the tabernacle represents both time and place. The outer court, where the altar of sacrifice was, represents the earth, where Jesus was crucified. Passing into the tabernacle itself, we move from earth to heaven. There, two apartments represent two phases of Jesus’ ministry as priest, the daily and yearly services mentioned below. These three (the court, the holy place, and the most holy place), and the services that were performed in each of them, form a prophetic timeline of Jesus’ work of redemption, spanning from His nativity to the final destruction of sin.

The Lamb.When John the Baptist pointed out the Messiah standing in the crowd along the Jordan river, he declared, “Behold the Lamb of God, which beareth away the sin of the world” (John 1:29, margin). Jesus was the One who all the sacrifices (mainly lambs) pointed to. He is even called the passover lamb: “Christ our passover is sacrificed for us” (1 Corinthians 5:7).

The Priesthood.Since they “serve unto the example and shadow of heavenly things” (Hebrews 8:5), the priesthood ordained in the time of Moses must also be symbolic. Indeed, when Jesus ascended to heaven, He did so as our “great high priest” (Hebrews 4:14). What does He do there? Just as earthly priests presented the blood of sacrifices and incense representing the prayers of the saints, “we have an advocate with the Father, Jesus Christ the righteous” (1 John 2:1), who “maketh intercession for the saints according to the will of God” (Romans 8:27).

The Daily Service.The fact that there is a heavenly priesthood proves that Christ’s work in the atonement was not finished at the cross, but that He still mediates for us today, pleading the merits of His sacrifice. This was represented by the daily sacrifice and the incense in the tabernacle.

The Yearly Service. Once a year, the high priest performed a special work of blotting out the sins of the people. This was figurative, since “it is not possible that the blood of bulls and of goats should take away sins” (Hebrews 10:4). In the prophecy of Daniel, spanning 2,300 years, we find a prediction of the work of Christ in the most holy place, which was foretold by the Day of Atonement in the tabernacle service, and which began in 1844. We are now living in the time of the Day of Atonement.

What was the purpose of all these representations? “Through the teachings of the sacrificial service, Christ was to be uplifted before all nations, and all who would look to Him should live. Christ was the foundation of the Jewish economy. The whole system of types and symbols was a compacted prophecy of the gospel, a presentation in which were bound up the promises of redemption.”2

Through a diligent study of the sanctuary, we will come to understand that the ancient tabernacle and its services are a picture of the ministry of Christ for His church during the Christian era, right down to the close of time. This doesn’t just relate to topics like the investigative judgment revealed in the book of Daniel but also to subjects like the seven churches in Revelation—represented long before their time by a golden candlestick in the tabernacle in the wilderness.

The services of Old Testament times are often called “a shadow” (see Colossians 2:17; Hebrews 8:5; 10:1). Some people might think that today it is not necessary to understand these shadows of heavenly things. But shadows are important. When light shines on any object, the shadow it casts makes that object more distinct. Studying the shadow of the cross today only makes the cross itself more vibrant to us.

Moses climbed down the mountain, carrying God’s blueprint with him. It would be just what was needed: the Lord’s plan to draw near and “dwell among” the people. He would teach them His character. He would help them understand the mission of the Messiah to come. But what did Moses find at the foot of Mt. Sinai? A people already seduced into idolatry—already reverting back to Egyptian cult worship, with its visible, tangible, enchanting, and sensual rites.

Yet today, is it any different? The conditions of society offer a striking similarity to the world in Moses’ time. The basic problems of society are the same. And the instructions written down by Moses can help us, too—only in a different way.

Today we do not offer sacrifices. We do not keep the festivals, and we don’t have a temple. These have met their fulfillment as “a shadow of things to come” (Colossians 2:17). But the truths taught in the “patterns of things in the heavens” (Hebrews 9:23) are still relevant today. What we need is to study the beautiful sanctuary message, presenting its symbols and parallels that make the gospel so plain.

How would you get the attention of the busy, work-oriented people of our modern world, long enough to reach them with the gospel? Let’s take a page from the books of Moses, and make that Old Testament message come alive for this generation.

For further study:

• Exodus, chapters 25–31.

• Hebrews, chapters 8–10.

• The Desire of Ages, pp. 22-26.

• The Great Controversy, pp. 409-422.

• Patriarchs and Prophets, pp. 343-358(Appendix, note 4).